GNP in constant prices in the first half of 2011 was €65,012 million, an increase of 1.0 per cent compared with the total of €64,337 in the first half of 2010. Furthermore, CSO figures published on September 22nd show other forces at work that provide grounds for hope that the recovery will become more robust. For example, foreign investment data show that in 2010, despite the barrage of bad publicity regarding the Irish public sector deficit international investors continued to display remarkable faith in the long term potential of the Irish economy.

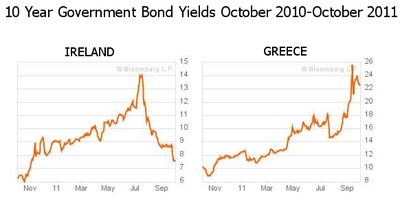

Synthetic 10 Year Yield (Bloomberg)

(Latest data in above graphic: October 3rd 2011)

(Latest data in above graphic: October 3rd 2011)

Foreign direct investment(FDI) in 2010 rose by 8 p.c. to a record €185 bn, matching the strong years for inflows of the early 2000s for the first time. The most telling statistic has been the decline in the Irish synthetic bond yield, which fell from over 14 p.c. at a time when it rose in Portugal and Greece.

In September, affected by the overall eurozone fiscal and banking crisis, the Irish bond yield has bottomed out, with 8.5 per cent, for now, proving the base for the Irish bond yield to test in the weeks to come. (Note: Since the time of writing (Mid September) the bond yield fell at the end of September by another 100 basis points, to test a new level of 7.5 p.c.). (See chart opposite).

For later figures, to assess the latest trends in Government bond yields (10 yr) amongst eurozone hi-deficit/bailout countries (sometimes referred to as PIIGS countries) see these links (lowest yielding countries listed nearest top of table):

SPAIN Government Bond Yield

ITALY Government Bond Yield

IRELAND Government Bond Yield (9 yr bond)

PORTUGAL Government Bond Yield

GREECE Government Bond Yield

It is clear that the crisis has moved on, to a wider eurozone arena, and, for Ireland, getting on with the job of restoring order to the public finances, while preserving confidence in the private sector among overseas investors and amongst SMEs will be crucial.

One important element in the confidence equation has become the value of the currency, and fears amongst corporate treasurers about the stability of banks has tended to be replaced by fears about the breakup of the eurozone, with Ireland amongst the periphery countries being ejected. Monetary stability is a bedrock of economic confidence, and therefore economic growth. When uncertainty attaches, as it does now, to the future value of a country's exchange rate, due to the speculation that now exists in markets regarding the continued existence of the euro, and the status of so called 'periphery' countries, (pejoratively described as 'PIIGS' sometimes) within the currency zone, some assurance as to future currency values in Ireland would be a definite advantage.

This is something over which the Irish Government can have some influence.

Were, for example, the Irish finance minister, or the Governor of the Central Bank to be asked the hypothetical question of what would Irish exchange rate policy be, in the hypothetical event of a breakup of the euro, a well thought out hypothetical answer could help.

That could involve an assurance that the Irish currency would be pegged at a certain fixed rate - e.g. returning to the old pre EMS policy of linking the currency in a no margins relationship with another currency - say, sterling, or, in view of Ireland's trade and investment relationships with the US dollar, an idea suggested last year by former Bank of Ireland chief Michael Soden.

Of course, the ability to issue statements such as this requires cash in the bank to back it up - something Irish Governments, up to lately have been short of. This was the problem Bertie Ahern faced in the early 1990s, in the Irish currency crisis, when, following a surge in Irish pound interest rates to over 25 p.c., he was forced to devalue.

But now things are beginning to change - the Central Bank is beginning to see cash trickling back in again, with the result that the Irish economy has moved into balance of payments surplus, (a modest €761 million in 2010), but likely to be more this year.

But even more than the financial equation, there is the economic logic that says that a devaluation of an Irish currency would make no sense – the fact that the country's foreign debt is denominated in foreign currency, and the exchange rate elesticity of Irish trade is less than for other countries (e.g. Iceland or Greece).

Thus, an assurance by an Irish finance minister in a hypothetical situation that he would ensure the stability of Irish money by linking the newly created Irish pound in a no margins relationship with sterling or the dollar - crucially, at the rate that prevailed at the moment of a hypothetical breakup of the euro could play an important part in underscoring financial and economic confidence.

Confidence amongst investors, consumers, and taxpayers is the key to the Irish recovery, and is the only possible source of growth - not the spending of expensively borrowed foreign currency through persistently high public sector deficits.