In the search for funding many more governments across the globe are turning to the bond market to meet their need for capital. In Sub Saharan Africa, for example, (Fitch Ratings now monitor no less than 16 countries ).

Furthermore, in the last year, countries such as Nigeria and Kenya have successfully launched long term debt instruments. Nigeria recently issued an inaugural 20-year bond, creating a benchmark for issuers and paving the way for commercial banks to launch their own bonds. Similarly, in April 2010, the Kenyan government announced that it planned to issue the first 25-year bond since the 1960s, as part an initiative to help financial institutions offer long-term debt products such as mortgages and project finance.

However, investors should exercise caution. The case of Argentina illustrates how governments can renege on previous commitments. The Argentine saga makes for enthralling reading but it has proved painful for those who are holders of the government’s debt. The sorry episode could portend a warning to investors in sovereign debt if other governments were to follow Argentina’s example; it would also mean that sovereigns would find it far more difficult to raise much needed funds.

It is worth highlighting some of the key points in this tale of woe.

Back in 2001, Argentina defaulted on more than US$81 billion in bonds. This was the most spectacular default ever recorded by a sovereign country. A year later, the government defaulted on a further US$800m debt repayment to the World Bank, which subsequently refused to consider any new loans to Argentina. In 2005, the government then offered a desultory debt swap at 27 cents-on-the-dollar on the outstanding US$ 81 billion it owed. Bond holders were horrified and resorted to lengthy litigation in the US , Germany, Japan and elsewhere throughout the world.

Following this debt restructuring in 2005 the Argentine legislature passed what was known as the ‘Locked Shut’ Law, which shunned bondholders’ legitimate rights. This Act prohibited the Executive Branch of government from reopening the debt exchange once it closed, or from settling with any bondholders who refused to accept Argentina’s ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ offer.

In 2007, a Venezuelan businessman by the name of Guido Alejandro Antonini Wilson was apprehended by customs agents in Buenos Aires carrying nearly US$800,000 of undeclared cash in a suitcase, allegedly money from Venuzuela destined for the presidential campaign of Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, wife of the then head of state Nestor Kirchner. Despite this embarrassment, dubbed the ‘suitcase scandal’, Mrs Kirchner won the election and succeeded her husband. She remains President to this day although her husband died of heart failure in October last year.

In April of last year President Fernandezr announced her government’s intention to repay the outstanding debts owed to Paris Club members (an informal group of creditors from 19 major economies which meets regularly in the French capital). Ironically, the Club takes its name from the crisis talks held in Paris in 1956 between a group of nations that were owed money by Argentina. The country certainly has a lot of form.

Last November, President Fernandez announced that Argentina intended to negotiate a resolution of Paris Club payment arrears without the help of the IMF. This move led to the temporary suspension of the ‘Locked Shut’ Law and at the time of writing Argentine officials are still trying to negotiate a deal with the Paris Club.

However, private investors should be alarmed at this turn of events, not only for what it means for those who remain holders of Argentine debt, but also for what it may signal to the private holders of euro denominated government debt issued by the Greek government and other beleaguered European peripheral countries.

If the Argentine government manages to secure a deal with the Paris Club this will scupper the rights of private government bond holders since a condition of any agreement would be that all bondholders receive the same terms. One can argue that this puts the interests of governments before private bondholders, which is inequitable.

As matters currently stand, bondholders are owed more than US$16 billion including accrued interest.

In order to regain credibility and a reputation for honest dealing, the Argentine government should meet these obligations. Until it does so, Argentina cannot access international capital markets. However, there are few signs that it intends to meet its debt obligations despite innumerable court actions in the US that have ruled in favour of bondholders. Only last month the US Supreme Court rejected Argentina’s appeal that sought to free ADR (American Depository Receipts) shares held in Banco Hipotecario with an estimated value of US$70m. These assets have been frozen since 2007 and it now looks as though they may be liquidated with a view to repaying bondholders.

The Argentine example, characterised by debt default, an aggressive debacle between bondholders and the Government and years of extensive litigation has immense implications for holders of distressed government debt issued by EU member states, notably Greece, Portugal and Ireland. Ever since Germany defaulted in 1948, every single sovereign restructuring has involved a country from the developing world . However, this pattern could soon change radically.

Given the huge public debts accumulated by these nations investors must have serious doubts as to whether any one, or all three, countries might default. As Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff point out in their recent book, Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, financial crises tend to be frequent and interlinked, while the long term effects of debt build-ups are rarely resolved without bouts of debt default, restructuring or inflation. Rather like Argentina, Greece has a regrettable history of form as far as creditworthiness is concerned. The authors point out that, ‘From 1800 until well after World War II, Greece found itself virtually in continual default’.

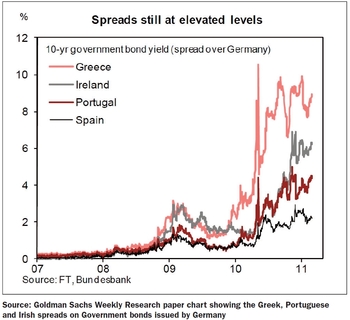

As the chart demonstrates several EU Member States are struggling to convince investors that they will be able to service their accumulated debts, despite attempts to tackle fiscal shortfalls. The spread on 10 year government bond yields compared with those issued by Germany reflects these concerns. Willem Buiter, formerly a professor at the London School of Economics and now Chief Economist at Citigroup has warned often that several Eurozone members will need to restructure their debts in the next few years.

Any Eurozone nation that does default or is tempted to go in for radical restructuring of its public debt may be tempted to emulate the Argentine example, riding roughshod over bondholders’ interests. Countries such as Greece may also be tempted to follow the Argentine precedent and prioritise the debt owed to sovereign countries. This would be hugely damaging to bondholders’ interests, and would be a further instance of ‘burning the bondholders’.

These pressures make the series of meetings scheduled in late March to address a “comprehensive solution” to the Eurozone debt crisis of pivotal importance. With spreads between ‘periphery’ and ‘core’ interest rates still very wide, on both sovereign debt and financial-sector securities, EU political leaders will need to adopt tough measures to convince investors that the dangers of restructuring or even default are remote. Yet with Spanish and Italian spreads back at the highs of late 2010, investors will need a lot of convincing.

Officials are working on a longer-term framework - the so called EU “comprehensive solution” - to address these pressures. The envisaged response centres on a European Stability Mechanism (ESM), a safety net that will offer conditional funds to address both liquidity problems in sovereign debt markets and, if there is a deep-seated solvency problem, a mechanism to smooth the necessary restructuring required. But the ESM will not be adopted before the middle of 2013 and Eurozone members may face a loss of confidence by global investors before then. Ireland was obliged to resort to the temporary European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) late last year after a string of denials by government ministers, but such a move may prove insufficient to prop up countries as large as Spain or Italy. Portugal, with its sclerotic economy and its inability to export goods and services, would probably survive courtesy of the EFSF, but only because it is a much smaller economy that has grown at a rate of under 1 per cent in the past decade.

A bizarre feature of the recent general election campaign in Ireland was a debate over the possibility of renegotiating the repayments and interest rates arranged on government debt. But such talk in practice is little more than rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic. The crucial issue remains: can these governments convince bondholders that they have the wherewithal to service their debts? Furthermore, the action required to rebuild fiscal stability in countries such as Ireland and Greece risks social unrest. After all, when the newly elected government in Greece applied the brakes last year there was serious civil disturbance in the streets of Athens, reminiscent of the riots in Buenos Aires in 2001 when Argentina defaulted. Meanwhile, the economic slowdown in Ireland has once again seen an exodus of young, talented people in search of employment opportunities and the devastating rejection of the ruling party in last month’s general election.

Leading investors’ doubts relating to the risk of default by a heavily indebted Eurozone member have led to a range of ideas being mooted, notably a proposal to encourage governments to adopt a policy of debt buy-backs, taking advantage of the discounts available on the market. But such an option still requires cash. The problem is that governments such as Greece and Ireland don’t have any, and they cannot resort to printing currency because they are members of a common currency. For the immediate future, at least, political leaders across Europe are likely to be confronted by a series of painful political choices. The temptation is to adopt the Argentine approach, but that would be a fatal mistake.